I am currently working on a novel, which is, in my personal opinion, an eternally wretched state, regardless of external circumstances: working on a novel feels fruitless in easier times, and it feels like an utterly asinine undertaking in the midst of multiple ongoing genocides and climate collapse and mass disappearances and—you know. Everything else. Of course I think joy is important, I tell other people this all the time—do what brings you joy, keep doing it, they can’t take our joy from us—but if all of us were better at telling ourselves the things we say to people we love who are not us, there would be no business for therapists in the first place. I don’t have a therapist. So thank god, then, for Leo.

I started reading Leo’s journals of his Youth because Charlotte Shane kept posting bits of them to Instagram, and I was caught, caught through the heart for good. Everyone loves a good writer’s journal—Kafka’s diaries (“Admittedly: Sadness is not the worst thing”); Octavia Butler’s motivational letters to herself, which white women love to repost without any sense of self-awareness, as is our wont; Ursula le Guin’s daily writing schedule (“After 8:00 p.m.—I tend to be very stupid and we won’t talk about this”), which invariably went viral whenever someone put it up on Twitter (RIP). This is certainly due in part to the comfort offered by the idea that even great geniuses suffered mightily in the composition of their canonical works (Kafka again: “The end of writing. When will it take me up again? […] Again tried to write, virtually useless. […] Complete standstill. Unending torments. […] How time flies; another ten days and I have achieved nothing.” Flannery O’Connor: “Please give me the necessary grace, oh Lord, and please don’t let it be as hard to get as Kafka made it.”). Stars—they’re just like us!

But I think it is also because they serve as a kind of analog-time antidote to the internet-era performance of the writer’s life—studiously ritualized, accessorized, posted and monetized, components available for purchase in the affiliate links—that registers for most of us as both entirely artificial and wholly unattainable, and which often does a considerable amount of work of context elision. The writer who has elaborate rituals, special garments, the writer who rises with the dawn and gazes out a window upon the mist-shrouded hills, replete with her great thoughts; the writer shrouded in cashmere wraps, her office resonant with the fragrance of her Dyptique writing candle. Or whatever. The writer seemingly insulated by her great genius from the tedious and unromantic drudgery of the day job, the day jobs—and how do we know how removed she is? The Vogue spread, the curated Instagram. How does one afford such a writing life? Usually by inheriting money or marrying it. No shame there, but that’s how it works. Unless we are very successful—and success, in this industry as in all others, is as much a function of luck and privilege as it is of skill and labor—we are required to engage in the relentless and often dissociative labor of positioning our work as a consumable product while insisting on the fiction that it is entirely divorced from the conditions of its production.

I am hardly the first person to hate all of it, but I do. I hate the skincare-regime interviews, I hate the awards churn and the new and notable table, I hate the cloying substacks, I hate being on substack, I hate that the only alternative to substack is paying $40 a month to send my own blog posts out twice a year to an audience of frankly not very many people through a platform that requires a computer science degree to sign up for, I hate watching extremely talented and brilliant people I care about lose their jobs over and over and over again as the entire infrastructure of the internet coagulates into a rancid stew of AI-generated fascism spon-con, and I understand why people do all of the things I hate, because I am doing many of them too, to the best of my limited ability. I too would like to make a living doing the one thing I am sort of good at. More than that, I want everybody I care about—which is everybody—to be safe and full and have a nice place to live and get to make art and go to the doctor. That seems like very little to ask, honestly. My humble desire: to remake the whole world. Well, bitch, I’m still waiting.

To be fair, young Leo was born into money too, although he didn’t have to post daily still lifes of his color-coordinated writing setup to maintain his activities. He went hunting a lot, he gambled, he wrote letters to pretty ladies, he undertook regimens of self-improvement and then abandoned them. (“The chief reason why I have begun to slacken is that I am beginning to realize that, much as I work at myself, nothing results from it.”) And he wrote all of this down, because the importance of a written record had got its hooks in him: “So many thoughts enter my head, and some of them appear very remarkable; they need but to be scrutinized to issue as nonsense. A few, however, are sensible, and it is for their sake that a diary is required, since a diary enables one to judge of oneself.”

Most of Leo’s judgements are quite harsh. Pages of his diaries set out a laundry list of his failings; for example: “March 16th—Rose reluctantly—sloth; wrote nothing, partly because I had nothing to write, and partly owing to sloth, to want of thoughtfulness. At the Beers’ showed diffidence, absence of mind; at Morel’s diffidence, absence of mind and gluttony; in the evening, lack of fortitude.” He is such a relentless fuckup, he notes, that he cannot even write down his fuckups without fucking up: “Even my journal of failings am writing hastily and without care.” Oh, Leo! Poor Leo, my Leo! He eats too much, he gets too drunk. He asks unimportant ladies to dance. He falls in love—“it happened at an evening party. I quite lost my head. I have bought a horse which I do not need.” He reads his writing aloud to his friends, and is morosely reassured of his incompetence by their reactions: “Can see that he is not pleased with [the chapters], though I do not assert that this is due to the fact that he cannot understand them, but the fact that they are bad in themselves.” They are bad in themselves because Leo is bad in himself. “I am not yet convinced that I lack talent,” he writes, unconvincingly. “Yet I seem to possess neither patience nor habitude nor clarity. Also, there is nothing great in my style, or in my sentiments, or in my thoughts. Am going to bed at 9.10.”

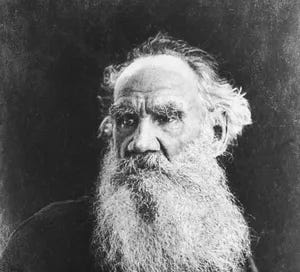

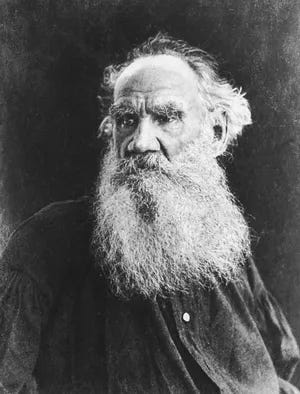

Leo!!!!!!! A bit older here, obviously

The obvious limit to the consolations of unformed baby Leo’s philosophies is that he went on to write Anna Karenina, whereas my own novel is, let us say, not going to light anybody’s way through darkness, although I hope it will at least provide a few hours of lavish distraction to the ten people in the world who have read The Secret History enough times to get my Donna Tartt jokes. There is, always, the tenuous and frankly delusional hope that this time, this one, at long last, will let me quit my day job(s), but I have been doing this a long time, and I was not uncynical when I started. So why am I doing this—why are any of us doing this? The thing is—what else are we going to do?

Well, and really this. I do not believe the work of art is salvation; I believe the work of art is to envision an alternative to the present real. Sometimes that alternative looks like a radical act of liberation. Sometimes that alternative is a liminal space for joy, or pleasure, or pain, or recuperation, or just the great relief of shucking this exhausting meatsack for a couple of hours. Sometimes that alternative gives us real sustenance, so that we can return to the more restorative political activities of casting off the brutal shackles of empire and seeking liberation for all beings. No book on earth can do that work for us, nor should any book have to. But a book can be a rung in a ladder, or a bridge. A book can be a window. A book can be a place of rest. A book—who knows. Maybe it can also be a door.

And here, now, even in this awful burning time of great terror and equally great stupidity, a silly little book can bring me joy. A great book can bring me outside myself to a place where I can see the horizon, to remember that there are other ways of being, other futures than the one we now face. “I have noticed,” writes Leo, “that when I am in an apathetic frame of mind a philosophical work never fails to rouse me to activity.” Me too, dear Leo—oh, dear Leo, across time and space and language, from one dumb dreamer to another—me too.

I’ll keep trying my best. I hope you do, too.

love,

sarah

WRITING LATELY: Just this fucking novel. I WILL move this newsletter off substack, I promise, I just have a lot of other things going on right now. You can order a print copy of my most recent published novel, The Darling Killers, here. It’s also an ebook.

READING LATELY: The dumbest shit you can imagine, and I don’t want to talk about it. I’ve been keeping an ongoing list of the good stuff I read in better times here.

I may be one of the ten people in the world who has read The Secret History enough times! When I have insomnia, I listen to the audiobook, so it’s osmotically embedded in my DNA by now.

This piece was a joy to read. Thank you.