If you are reading this in the Northern Hemisphere, we have come together to the longest night. This is a time of year I ordinarily love, although in the last months I have felt not so much as though I am moving toward the quiet, restful dark as traveling across a terrible wasteland outside of night or day, where the sky is only ever a rust-colored, nauseating twilight and nothing grows in the barren, desiccated earth. It is hard to hold hope in these times. There are days where I cannot, and so I must ask you to hold it for me. And on the days that you yourself are unable, I can carry it again. So we move forward. Our work now is to live as though we already inhabit the world we are waiting for. Our work now is to attend to the suffering of other beings, and to attend to the suffering within ourselves, so that we do not inflict it on those around us. Our work now: We know it. None of us are free until all of us are free.

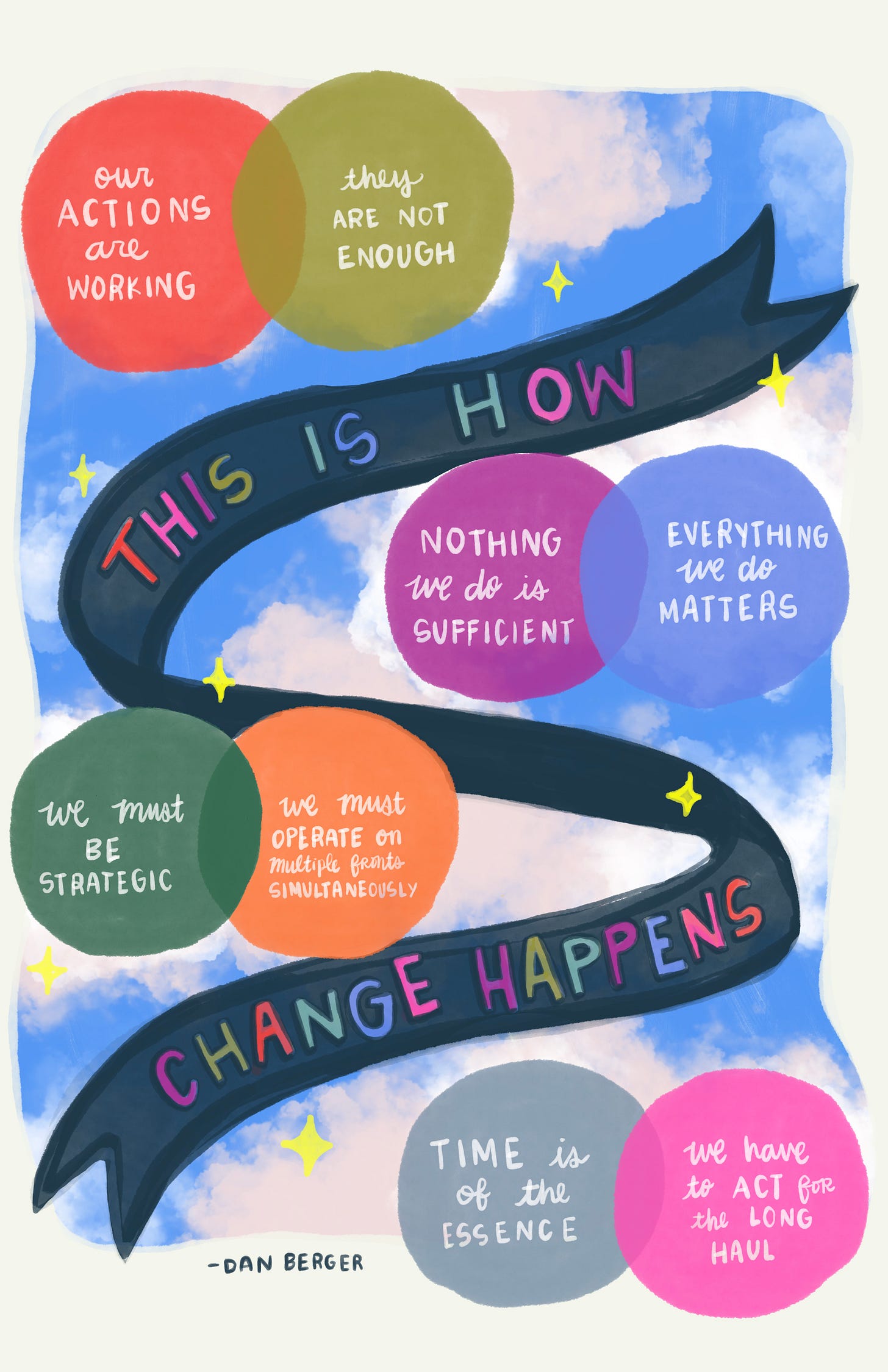

“Nothing we do is sufficient,” wrote the historian Dan Berger a few weeks ago, “and everything we do matters.”1 I am talking about Palestine, but I am also talking about everything, because the genocidal, world-wrecking terror of empire is not confined to the Gaza Strip. It lives in prisons and in presidents, in corporations and in capital; it thrives in the police, in weapons factories, in deep-sea drilling rigs, in cobalt mines and in cop schools; it writes policy, it passes laws, it invests; it invents nation-states and borders; it generates commerce; it leaves migrants to drown in the Mediterranean and die of thirst in the desert; it warps our weather and spills ruin; it seethes through every available fissure into every place we hold sacred on this earth. It has its bloody teeth in all of us and in everything and everyone we love. Nothing we do is sufficient. Everything we do matters. And let us never forget that horror is not our only history. Many of us have already survived apocalypses. Many of us hold long traditions of resistance in our lineage. Many of us are well-practiced in finding joy in the face of all the forces that seek to suppress it. Many of us have already grown what Herbert Marcuse described as new “organs for the alternative.”2 “The practice of freedom is difficult,” writes the sociologist and abolitionist Avery Gordon,

and it can be overwhelmed by despair and depression, but it is also joyous for it is, in short, the process by which we do the work of making revolution irresistible, making it something we cannot live without. […] Making revolution irresistible. This is how we make the best history we can now, which is only ever when we have a chance.3

The nights between the winter solstice and the new year are called Rauhnächte in Germany—wild nights, a time between times when the veil is thin. The dead cross over to walk with us under the fierce stars. We take their hands. We are clear to one another in the moonlight. We say their names. We keep their stories in our mouths, in our bodies. We dream.

Artwork by Laura Chow Reeve

The meditation teacher Tara Brach tells a story of a princess who, due to the misfortunes of her family, is married off to a fearsome dragon. A wise woman in her village (there’s always a wise woman in the village) counsels her to wear ten beautiful gowns on her wedding day, one on top of the other. After the wedding feast (there is always a wedding feast), the dragon carts his new bride off to his bedchamber. She tells him that as she must undress, so must he. “Okay,” the dragon says. The princess (it’s always a princess) takes off her outermost dress, and the dragon, who is accustomed to shedding in the manner of reptiles, removes his outermost layer of scales. The princess unfastens the next dress, and the next, and the next. The dragon finds he must claw away more and more of his skin, but the princess is relentless (it’s always on the princess to be relentless). This process is terribly painful. With each sloughing, the dragon becomes more tender. And when the princess takes off her tenth dress, the dragon tears away the rest of his scaly exterior and reveals himself to be (of course) a prince. (There’s always a prince, if you work hard enough.)

This is easily read as a story about receiving grace, the necessary pain of transformation, and the path to inner freedom, obviously, and I do not mean to be flippant. I love Tara Brach. But the version of this story that I prefer is the one in C.S. Lewis’s The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, the third published book of his Narnia series. In it, the younger Pevensie children, Edmund and Lucy, are reunited with their good friend Caspian, the king of Narnia, and sail eastward with him aboard the ship the Dawn Treader in search of the seven Lost Lords of Narnia. They are joined by their recalcitrant cousin, “a boy called Eustace Clarence Scrubb, and he almost deserved it.” We know Eustace will be unpleasant because we are told in the book’s opening paragraph that his parents are vegetarians and minimalists and because Eustace dislikes sport and his saintly cousins, who are continually rescuing the kingdom of Narnia from some peril or another.4 At first, Eustace acquits himself poorly on the Dawn Treader. He gets seasick; he cries; he picks a fight with a talking mouse, and is ignominiously defeated by it in battle; he shirks his duties aboard ship. (In fairness to Eustace, it is not his fault nobody has ever taken him sailing before, and sailors can be real dicks to people who don’t know what they’re doing on a boat, and the fifth time somebody tells you that seasickness is all in your head while you are puking over the ship’s rail you too might be seized with the urge to engage them in a swordfight, but I digress.)

The Dawn Treader weathers a violent storm and subsequently makes landfall on an island to undertake repairs. Eustace, unwilling to participate in these labors, creeps off into the forest. A fog rolls in, and he becomes lost in a sinister valley. A sudden downpour strikes, and he hides in what turns out to be a dead dragon’s cave to escape the rain. He is delighted to find the dragon’s hoard, slipping a jeweled armband over his wrist and stuffing his pockets full of gold. Eventually, he falls asleep. When he wakes up from “sleeping on a dragon’s hoard with greedy, dragonish thoughts in his heart,” he finds that he has “become a dragon himself.”

It is here that Eustace comes to regret his past transgressions, the terrible burden of his obstreperous self. He reviews his poor behavior, his whining, his many complaints, his insults to the Pevensies and the talking mouse Reepicheep. He encounters, for the first time, the absolute mortification of being. He comes face to face with shame. He flies in his dragon shape to where the Dawn Treader is moored, and manages to convey that he is Eustace, changed into a dragon, before anyone runs him through with a spear. His companions like him better as a dragon, and, spurred by their new magnanimity, he does his best to be helpful: starting campfires with his breath; provisioning the ship with wild swine; heating chilly members of the crew with his warm bulk; retrieving a massive downed pine tree for a new mast; taking his comrades for sightseeing flights. In his long lonely wolf hours the mouse Reepicheep, newly his friend, comforts him in his despair.5

And then one night the lion Aslan comes to dragon-Eustace in the moon-silvered dark and brings him to a beautiful mountaintop spring and tells him he can bathe there, but he must first undress. No dragons allowed in Aslan’s bathtub. Eustace scratches off his loose scales, but Aslan is not satisfied. Eustace must dig deeper, and deeper, peeling away his dragon-mantle, and it is still not enough to free him. Aslan steps forward, and Eustace subjects himself to the lion’s claws. “When he began pulling the skin off,” Eustace says later to Edmund, “it hurt worse anything than I’ve ever felt.” Aslan tears away the last of Eustace’s dragonness, and at last Eustace is able to be baptized in the magical spring.6

I like this version better, and not just because the companions sail their way to the extraordinary edge of the world. I like it because as a dragon Eustace engages for the first time in the work of being useful to his community, and there are a lot of things a dragon can do that a person can’t. A dragon breathes fire; a dragon lays waste; a dragon protects what it loves. A dragon carries its friends to a place where they can see the whole world unfolding beneath them, perilous and beautiful all the way to the blue horizon. A dragon has money, and as long as we have capitalism—not much longer, now, but long enough to inconvenience us—money helps us keep each other safe. I would rather be a dragon than have to trick one into becoming its tenderest self, and I would rather be a dragon than a prince.

And I like this story because, in the end, Eustace is not a prince either; he is returned after his transformation to being only himself. He is an ordinary person, learning to be aware of his own flaws and remorse and courage and patience and capacity for loving and being loved, a person undergoing the lifelong, terrible, wonderful work of being alive to the whole presence of the world and all its attendant sorrows and joys. He is a person who does a better job of being a person once other people start being kind to him. He is a part of his community, even when his community is irritating and makes him go about on boats. He gets back on the Dawn Treader. He goes sailing. He concedes that sunsets at sea are indeed magical.7 With his companions, he finds the very edge of the known world and all its radiant light. He comes home again after his adventures, still himself, but a little braver, a little more willing to listen when other people tell him stories of worlds he had not imagined could exist. I like to think that Eustace always remembered how it felt to be larger than he thought possible, to take care of others with his dragony might. To be strong enough to carry anything. To have wings.

Sometimes we are called to be dragons in the service of revolution, but we are always still ourselves, imperfect and loved and learning. “In a sense,” writes mindfulness teacher Kaira Jewel Lingo,

our culture, our society, is dissolving. We are collectively entering the chrysalis, and structures we have come to rely on and identify with are breaking down. We are in the cocoon and we don’t know what the next phase will be like. Learning to surrender to the unknown in our own lives is essential to our collective learning to move through this time of faster and faster change, disruption, and breakdown.8

We go together into the long dark. We care for each other. Let us remember in our waking and our sleep that the new world is alive within us. We carry its seeds in our hearts. Already, our seeds are putting out roots. Already, they have been forests.

Nothing we do is sufficient, and everything we do matters. Tonight, we are dreaming. Always, we are here.

with love, in light and in darkness, from the river to the sea,

sarah

WRITING LATELY:

Well, to be quite honest, I didn’t do that much. I wrote about a mysterious undersea mountain and vampire moms for Tor.com. You can order a print copy of my latest novel, The Darling Killers, here. It’s also an ebook.

READING LATELY:

“Haneen once compared Palestine to an exposed part of an electronic network, where someone has cut the rubber coating with a knife to show the wires and currents underneath. She probably didn’t say that exactly, but that was the image she had brought into my mind. That this place revealed something about the whole world.” Isabella Hammad, Enter Ghost

“The war on Palestinians has always been a war of language, a war of propaganda and PR. It is a project that has relied on western military support since its inception. Without the consent of western publics and without that military support (to date, $172bn in US largely military aid and missile defence funding; Israel is the largest international recipient of US aid bar none), Israeli apartheid would not survive. So these do matter. Language is not small, even though, in our hearts, of course, what actually matters most is this terrible brutal waste of human life.” Isabella Hammad in conversation with Sally Rooney at the Guardian

“Magnolia moved directly from college to the forest. They have been cooking in the living room for months, mostly basic sustenance to keep the campers happy, but also for big events, which are happening increasingly often as the movement agglomerates allies. Even more than the police, Magnolia knows, the enemy is hunger. Back in November 2021, when a Muscogee delegation came to do a stomp dance—the first ceremonial return to this land since walking the Trail of Tears, we heard—the forest cooks made mashed potatoes and nine vegan pies and wild rice with black Weelaunee walnuts, and stew from a frozen roadkill deer, which took too long to thaw, so Magnolia had to hack it into pieces with a pickax. ‘How long has it been since these trees heard our language?’ asked the Mekko to nodding allies. After the ceremony, the Muscogee dancers turned out to have already eaten, so the forest defenders ate venison like kings all week.” “Not One Tree,” N+1

“Germany’s commitment to memory is undeniably impressive; no other global power has worked nearly as hard to apprehend its past. Yet while the world praises its culture of contrition, some Germans—in particular, Jews, Arabs, and other minorities—have been sounding the alarm that this approach to memory has largely been a narcissistic enterprise, with strange and disturbing consequences.” “Bad Memory,” Jewish Currents

My friend Molly sent me this. I thought you might like it:

I came to these words via Mariame Kaba’s wonderful newsletter, Prisons, Prose & Protest.

Herbert Marcuse quoted in Avery Gordon, The Hawthorn Archive: Letters from the Utopian Margins

Ibid.

It’s always Satan.

“On the evenings when he was not being used as a hot-water bottle he would slink away from the camp and lie curled up like a snake between the wood and the water. On such occasions, greatly to his surprise, Reepicheep was his most constant comforter. The noble Mouse would creep away from the merry circle at the camp-fire and sit down by the dragon's head, well to the windward to be out of the way of his smoky breath. There he would explain that what had happened to Eustace was a striking illustration of the turn of Fortune’s wheel, and that if he had Eustace at his own house in Narnia (it was really a hole not a house and the dragon’s head, let alone his body, would not have fitted in) he could show him more than a hundred examples of emperors, kings, dukes, knights, poets, lovers, astronomers, philosophers, and magicians, who had fallen from prosperity into the most distressing circumstances, and of whom many had recovered and lived happily ever afterwards. It did not, perhaps, seem so very comforting at the time, but it was kindly meant and Eustace never forgot it.” I am not sure if this passage is intended to be quite as funny as I find it.

Yes, Aslan is Jesus; no, C. S. Lewis was not known for the subtlety of his metaphors.

I might have made that part up.

Kaira Jewel Lingo, We Were Made for These Times

The expanse of your writing while clearly focused on one theme is so beautifully done. As I take stock of where my fears, hopes and efforts for the world lie (a nearly daily occurrence), this piece calls me to take action, and rightfully so.