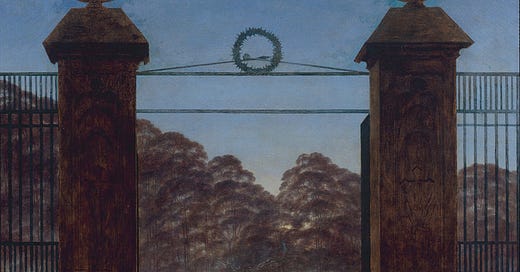

September fifth would have been the 250th birthday of the painter Caspar David Friedrich if he were still alive, which, of course, he is not. Three different exhibitions in his honor have been presented this year in Germany, in Hamburg, Berlin, and Dresden; the Hamburg and Berlin shows sold out before I could get tickets, but we went two weeks ago to Dresden to see the third, a collection primarily of his landscapes.1 Friedrich spent much of his life in Dresden, and is buried there in the Trinitatis Cemetery, whose entrance pillars served as the model for his painting Friedhofseingang [The Cemetery Entrance].

Caspar David Friedrich, Friedhofseingang [Cemetery Entrance]. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Had I so wished while I was in the city, I could have walked to the site of the slaughterhouse where the American soldier Kurt Vonnegut was imprisoned during the 1945 firebombing of Dresden, emerging afterward to what he described to Rolling Stone in a 2006 interview as “carnage unfathomable.” The Germans put Vonnegut and his fellow POWs to work gathering bodies, he said, but “there were too many corpses to bury. So the Nazis sent in guys with flamethrowers.”2 He spent twenty-three years working on a book based on this experience, publishing the now-classic anti-war novel Slaughterhouse-Five in 1969. The book made him a millionaire. In his autobiographical 1981 collection Palm Sunday, he wrote:

The Dresden atrocity, tremendously expensive and meticulously planned, was so meaningless, finally, that only one person on the entire planet got any benefit from it. I am that person. I wrote this book, which earned a lot of money for me and made my reputation, such as it is. One way or another, I got two or three dollars for every person killed. Some business I'm in.

I could have walked to this place, but I did not. It is not a slaughterhouse anymore. It’s a brewery. You can’t go inside. It is true that there is no meaning to be had here. That’s just how it is.

Caspar David Friedrich is today one of the most famous German painters in the world, but this was not true in the time in which he lived. He was born in 1774 at the edge of the Baltic Sea, in a town not far from where I live now. His mother died when he was seven; a sister died when he was eight; another when he was seventeen. When he was thirteen his younger brother fell through the ice crusting a frozen lake and drowned in front of him, possibly in the course of trying to rescue Caspar David Friedrich from the same fate. In addition to the landscapes for which he is particularly renowned, he painted a lot of cemeteries. In 1798 he moved to Dresden; early in his career, he enjoyed a period of success, but his work fell out of favor, and he died in poverty, a recluse. His work was recuperated by the Surrealists at the turn of the twentieth century, propagandized by the Nazis, embraced by Walt Disney. In reproductions, the radiant translucence of his paintings is condensed into something approaching kitsch, easy to interpret as an oblivious nostalgia for a golden country stripped of history and difference, the annihilating utopia of fascism. No wonder, one thinks, Disney—who welcomed the Nazi filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl to his studios in 1938, a month after Kristallnacht3—loved them. Perhaps it is dangerous, one wonders, to love them too.

But in person, the paintings are something else entirely. Their extraordinary melancholy is a palpable force. They are filled with a luminosity that defies categorization and is impossible to photograph. Cemeteries and horizons, mist-shrouded stones, wine-dark seas, mostly devoid of human presence. If there are figures in the paintings, their backs are nearly always turned to the viewer; they are moving away into the distance, they are looking at something else, caught in their own society, unreachable. The painter is always alone. The isolation of the painter seals the viewer into her own remove. The details of the paintings—trees, mountains, gravestones, waves, fog—convey at first the impression of nearly photographic realism, but the longer one looks, the more unreal they become: the arc of the clouds improbable; the ships on the horizon looming in a perspective that cannot exist; the moon enormous and too much more than clear. It is no wonder the Surrealists claimed them; their uncanniness insists on itself. The German word Sensucht is commonly translated as nostalgia, or pining, but it means something larger; it is a word pieced together, literally, out of yearning (Sehn) and addiction (Sucht). The endless craving for an imagined horizon. The longing to return to a place that has never been.

Caspar David Friedrich, Das Große Gehege bei Dresden [The Large Enclosure Near Dresden]. My photograph

Imagine the power to transmit a grief so massive across centuries in the line of a cloud, in the color of a night. I think it must have been a terrible thing to live with such a gift. But what a miracle it is to witness; what grace it is, to be thus seen. In the presence of these paintings I felt myself overcome. The extent to which I have become porous in the last year is remarkable. At times it is difficult to keep breathing. But I do. Really, I will be fine. That seems in itself a great injustice. Does writing this down change anything? I have long since come to a place where language is insufficient to name what it feels to be alive in this time. Who am I to try? I have never known a sky full of fire. I live in the house of empire. Its walls are rotten. But its foundation goes all the way through the earth.

Caspar David Friedrich, Küste bei Mondschein [Coast by Moonlight]. Source: Wikimedia Commons

On the uppermost floor of the Museum of Military History in Dresden there is a small exhibit focused on the bombing. One can follow the narratives of various people who survived and did not survive that night. “I was ashamed we stooped to the level of the Krauts,” an American fighter pilot who flew in the raids is quoted as saying. This shame had not been sufficient to prevent him from going so low himself. Perhaps his shame did not come until afterward. I could not explain why this line had such an effect on me until a day later, when I realized that, of course, there has never been a low to which America will not stoop. There is no low that will ever shame us. Another story in the exhibit followed a Jewish boy whose family had spent the war in hiding in an apartment in the city; time was running out; the only thing that would save them from the camps, his father said, only half-jokingly, was the bombing of Dresden. The bombs fell that night.

In the morning the boy awoke in the ruins of the family’s apartment, surrounded by the broken bodies of his father, his mother, and his sisters. He made his way to the street outside, where he found a puppy tied to a post, the only other living being in a sea of rubble. He made his way, with the dog, to shelter and what would turn out to be a long life. He worked in an automobile factory and had many children. I became preoccupied with the fate of the dog, which was not specified. Thinking of the dozens of pictures and videos I have seen now, of Palestinian children fleeing and fleeing and fleeing again, clutching tightly to their pet cats, a little girl solemnly telling the person filming her that her cat is her responsibility, that if the cat dies it will be her fault, because she has been tasked with the cat’s protection. The fate of the cat is not specified. The fate of the child is not specified. The fate of the person who filmed the child and her cat is not specified. But I know the odds. I am paying for them. My name is on every bomb that falls.

Some business I’m in.

We took the oldest suspension railway in the world to the top of a hill at the edge of the city, a hill crowned with a thicket of mansions. Many of these houses are very old. None of them needed rebuilding after the war, because the bombs did not touch them. It was a sunny day, impossibly bright. From that hill you could see the whole city. I thought of the people in those houses in February of 1945, looking down at carnage. How the sky must have glowed with all the unholy colors of hell. How those people must have been frightened. How much of a relief it must have been, in the midst of this terror, to realize they were safe behind their walls. Away from the railway station, the hilltop was silent. The houses so still they might have been empty. Very wealthy people, I have learned, often prefer not to be seen.

The view from the hill.

It is not possible to reconcile what should have been and what was. It is not possible to reconcile what is and what should be. But here we are, living in it. We, you and I, will almost certainly survive this moment. Many people will not. I am crying in front of a painting. Somewhere else, the bombs are falling again. I am living on the hill looking down into the inferno. The bombs are manufactured in my house. One day its walls too will crumble. From the ruins, something else can finally bloom.

No hills, no inferno. All the cats are playing in the grass. See how soft their fur is! All the children are sleeping; all they know is joy. In their houses, their families, whole and laughing, wait for them to wake. In their houses, the cupboards are full. The sky in this land is clear. This is the easy country of my dreams.

Sometimes I put down my phone. I look away. Outside my window, the sun is shining and the cool air is moving inland from the sea. The waxing moon a pale crescent against blue. What color is this sky? It is the color of a safety that all beings should know. I think what gift I’ve had has left me. What a luxury silence is now.

love,

sarah

WRITING LATELY:

Once again, I am working on a novel. Ugh!

READING LATELY:

“…I’m less interested in ‘what happened to you’ than the transmission of a feeling, something breathable and contagious, a vast, raw, yet untethered emotion, that’s how I want to be seen and how I want the writers I love to be seen, not for the self but for the ecstasy, the writerly ecstasy, caught and passed on like an electric charge.” —Sofia Samatar, Opacities

“You see, when one’s young one doesn’t feel part of it yet, the human condition; one does things because they are not for good; everything is a rehearsal. To be repeated ad lib, to be put right when the curtain goes up in earnest. One day you know that the curtain was up all the time. That was the performance.” —Sybille Bedford, A Compass Error

A version of this exhibit is coming to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City in 2025.

https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-features/kurt-vonneguts-apocalypse-1235072885/

https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/movies/movie-features/leni-riefenstahl-hollywood-1235001606/

bravo